In September 2025, I permanently lost my childhood home. They tore down the hundred and fifty-year-old brick schoolhouse where my brother, my sister, and I were raised to adulthood.

When I was five, back in 1947, my father decided to buy a one-room brick school house to remodel and make it the family home. The schools were all consolidating into larger new facilities and the commissioners in Darke County, Ohio had decided to sell off all the old single-room school properties on the cheap. Dad paid less than $4000 for the almost two-acre acre site with all the buildings intact.

250 years ago, the roads where the school was built were little more than wilderness paths. Arthur St. Clair and Anthony Wayne both marched their troops past that intersection, which later became the school. I found an old one-handed knife in the garden that had been dropped by one of the soldiers back in the 1780s.

The first settlement in Darke County was made a mile west of the school on Boyd Hill near Boyd Creek. I was lucky enough to live on that very spot when I returned from New York City to Ohio for a few years.

A marvelous Victorian-styled Children’s Home had been built at the turn-of-the-century for the orphans and hard-pressed families of school age children. It stood just north of us until that too was torn down in the name of progress and efficiency. The big old buildings were hard to heat and used coal. The Children’s Home had its own school . It could easily be seen from our home. Some of the children there became my playmates for many years,

One day it was there. The next day, it was gone.

The children walked to school in the old days as there were no buses or cars.The schools were situated every few miles. Many had a belfry and a bell to summon the kids from the neighboring farms.

When we became the owners, three or four grand pianos had been stored inside the school. They had been taken from other local schools. All of them were in terrible shape and had seen severe weathering. One of the first things Dad did was to take them out and burn them after saving the lead weights.

It seemed to me, though I was six, that burning these pianos was not a good thing. The pianos, like the school, had outlived their useful lives, but I could not understand that at that point. I had hardly any concept of time. Time was associated with functions like time to get up, time to go to bed. time to eat, and time to go.

The next unwanted objects to go were the inch-thick genuine slate blackboards placed on the north and south walls. They were carefully stacked near the two brick outhouses at the rear end of the lot. There was one privy for the boys and one for the girls. A path of cinders from the coal-fired stove led to the privies. As soon as the plumbing was installed, the outhouses were torn down. The old bricks were carefully stacked in patterns to keep them from collapsing.

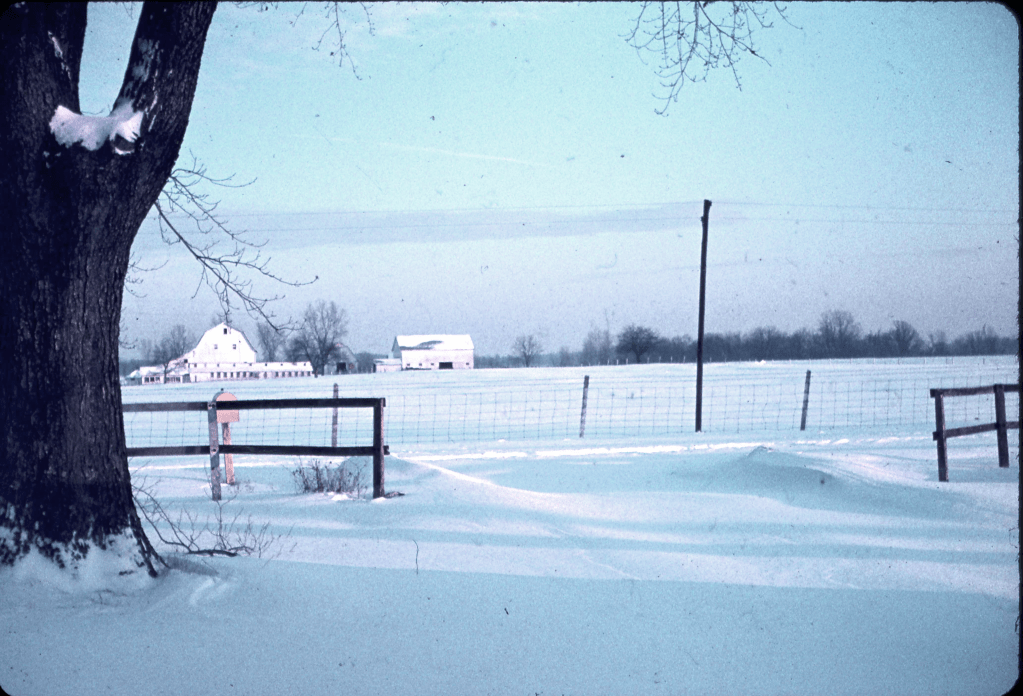

The yard was like a beautiful little park. The grass was a thick, hearty bluegrass. There was room for a large garden. The yard was surrounded on both road fronts with a two-rail wooden fence. A wooden coal and woodshed was on the north side. Three tall elm trees – whose branches began twenty feet off the ground – graced the property. One of these stately trees stood directly in the center. It was the first to fall from the Dutch Elm disease.

Dad roped one of the tall elm branches for a twenty-foot rope swing. There were two buckeye trees, a shagbark hickory, two large oaks, and half a dozen maples trees, including at least one sugar maple that we sometimes tapped for syrup.

Above is a picture of another school about three miles east of our schoolhouse. This was called the Knick School and is presently owned by a coon hunting club. The construction of these buildings was much the same. Three-foot thick brick walls on a wedge-shaped limestone foundation that started eight feet deep. The interior walls were plastered with 14-foot high ceilings. All had a date plaque in the front, a recessed front door with the traditional rounded top windows, standing seam steel roofs, a wooden fence and a shed. The rafters were true 2×6 timbers and the ceilings were 2×12, all made from local hardwoods.

Our schoolhouse was built in 1885. It was called the “Mannix” school because it was named after the locals who lived nearby. Jim and George Mannix were neighbors in the 50s. Their farms bordered on the schoolhouse property. Jim was a tall, thin bachelor farmer who helped care for Matt Rife. Jim owned and farmed the land Old Matt occupied. Matt could be seen walking along Highway 127 most every night. He seemed to walk to town daily. Matt lived in an unpainted rural shack with a barn behind painted with a “CHEW MAIL POUCH TOBACCO” ad. It was a Celina Road landmark. We often saw him in the dusk, wearing his gray overcoat and his Fedora, shuffling back home from town.

Half a mile to the east on the Children’s Home-Bradford Road, our neighbor, Pete McVay, lived in a leaning old two-story log cabin that looked like it would fall over at any time. He and his brother had a store on Broadway. Pete drove back and forth daily in his black 1920s Model T Roadster.

Dad enlisted my Grandfather–a bricklayer and stone mason–to help with the brickwork and to drop the ceilings to eight feet. To do this, they ran joists over the long windows, bricked up a few windows, and the front door. This removed any possibility of a later historical renovation.

I was not too upset about the loss of the front door, as this door was what introduced me to the concept of ugliness. The paint was scaly, twisted, gray lead paint that had been peeling off for years. The summer sun sharpened the image before my eyes, dust motes floated in the dusty air the smell of broken plaster invaded my nose––and I thought it was ugly––bad looking. I had never considered anything ugly before that.

Bonehead Allred, a cousin of my Dad’s, dug a false well for the pumps and pipes and ran pipes to the house. Even as a first grader, I wondered why anyone would call him “Bonehead”. He seemed friendly and smart to me. This was my introduction to type-casting social shaming.

The plumbing went in, partitions went up. drywall was crucified on the furring strips. We moved in long before my father’s original vision for the place was complete. We did have running water but the water heater had not been installed and the drywall was left unprimed. It seems like it took many years for Dad to get back into the remodeling mood. Much of the interior finish was left for me to do when I was old enough to do it.

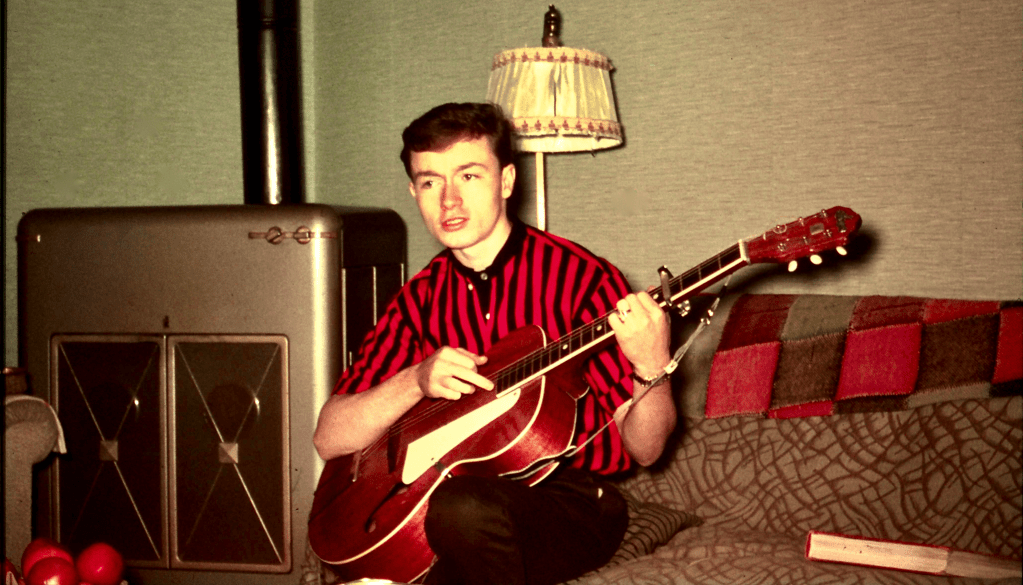

Nevertheless, we made the place a comfortable home that lasted for thirty years. We still relied on an oil space heater. Winter mornings became a race to the stove to warm our clothing.

My mother never liked living there. It was a lot of work to care for the huge yard and gardens while still trying to finish the remodeling.

Friends visited and played croquet, badminton, and horseshoes in the great backyard. I would return many holidays after I left home and bring my New York City and Chicago friends to a sumptuous dinner at the country kitchen. They always had a wonderful time.

Dad finally realized he no longer had the energy to complete his vision and settled down to his historical research and cataloging old county cemeteries for posterity. My father died in 1974. My mother did not want to remain in Greenville. She sold the household items and antiques at a big estate sale in the backyard and moved to Denver, Colorado. Her sister had inherited her father-in-law’s home. It was empty and ready for Mom to occupy and start a new life.

The schoolhouse sat empty for twenty years while the family established Colorado as their new home. Finally, my mother decided to sell it. A real estate agent bought the land and let it sit empty for another twenty years.

I had hopes it cold be saved, It would be a fine museum. Others thought so as well. Time ran out as it tends to do on all. In late September of 2025, they tore the building down.

I knew it would happen, but I couldn’t live there or save it. Ten years before I had written a poem about what I envisioned.

“They are tearing down

my childhood home today,”

he said, wishing instead

he were already dead.

“I should not watch.

It is a sad thing to see,”

he thought, thinking softly of the past,

wishing it could forever last.

“I wish I could have done more to save it,”

he mused, feeling the blues

as it oozed from the news.

“I ate watermelon at the kitchen table,

sweet as summer’s breath,” he said,

tasting the juice that his mind reproduced.

“We had many a memory in that house,”

he understated,

watching as his

reality was castrated.

“I wonder it I was happier

back then than now,”

he exclaimed, unashamed

that he had no fame.

“Probably not,” he said to himself,

knowing he had not mastered laughter

in the face of disaster.

“Some folk’s homes become museums,”

he pondered as his thoughts wandered. “

I was never that important,”

he concluded, as he brooded.

The old trees were destroyed. The site was leveled like a parking lot. Now I feel even more regret. We live in an era where greed dominates, and the past, for many, is simply a quaint memory easily forgotten. Progress is shiny and new. The past continues to age as it deteriorates with time. The old school will join the great heap of forgotten histories and stories unremembered, as will we all.